My novel, Prairie Hill, has its origins in a short story first published in Fan, a baseball literary magazine, in 1992. Although “Jimmy Lathrop” is not an autobiographical tale, the setting and atmosphere come from my own experiences playing high school baseball in the late 1970’s. No doubt the strangest game I ever played took place against a reform school run by monks. We wore old-fashioned flannel uniforms, but the reform school team donned tattered uniforms dating from the 1950’s. Their baseball diamond featured an outfield that no one had mowed yet and a rocky infield with ruts and pits, a non-existent pitcher’s mound and a rusty chain-link backstop.

After publishing “Jimmy Lathrop,” I kept thinking about the central character and I began to take notes about his life, sketching out a character study, meeting his family members, exploring his world. A few years later I passed through a quiet, dusty small town in Wisconsin. Looking out the window, I spotted a forlorn-looking black and white Holstein cow, waving to passersby, inviting them to stop at a local inn for the “best burgers in town.” The image stayed with me and, in time, came together with the mysterious Jimmy Lathrop, only he wore a chicken costume instead…

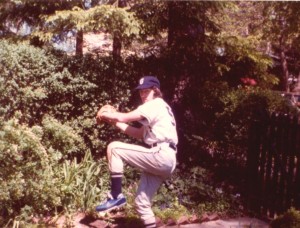

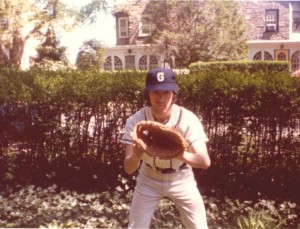

My brother Jeremy graciously rummaged through my mother’s meticulously kept photograph albums and scanned a few photos of me in my ball playing days, used here to illustrate “Jimmy Lathrop.” As an avid collector since the age of six, I took the opportunity to try out some of my favorite baseball card poses!

Jimmy Lathrop

Pulvey parked on a dirt lot next to a couple of baseball fields. Behind a thin line of trees and up on a hill, I saw a huge, gothic stone building with slate-shingled turrets.

“Come on guys! Get a move on!” yelled Pulvey. “Let’s warm up. The other team ain’t here yet.”

We shook out our travel-weary legs and trotted past the rusted chain link backstop and onto the lifeless ball field. I shagged some fly balls out in right, but grounders were hopeless. The grass grew above my ankles.

“This place sucks!” shouted Snitzer in center, when a grounder stopped short ten feet in front of him.

“Shut up, Bump,” came Pulvey’s voice from home plate. His words, and the next ball he swatted, died with the wind that kicked up dust and candy bar wrappers.

The sun had snuck behind clouds when the St. Boniface team filed down the hill to the filed, followed by a monk in a brown robe. We Emory Friends Schoolers crowded onto a bench, and watched them play pepper. Their ratty flannel uniforms were too big or too small, depending on the player. They seemed unfriendly…and strangely silent.

Pulvey walked over to the monk and said, “I’m Coach Pulvermacher,” and held out his hand. The monk ignored it. “We will play seven innings,” was all he said. They exchanged lineup cards.

Bump nudged me as their pitcher took the mound and fired some in. “Look at this dude. He probably shaved when he was ten.”

The St. Boniface pitcher was well over six feet and dark-faced, pockmarked. He threw one hard that got past the catcher and lodged in the backstop. “Be glad that’s not your baby face,” said Butterfield, our second baseman.

The umpire, whose blue shirt strained over his immense belly, shouted “Play ball!” I was the first batter up and stepped into the box. I felt the sweaty presence of the catcher next to me, and behind the cage, the monk. I nearly fell on my butt when he growled, “Hum it in there, Jimmy!” The first pitch was a called strike. The monk kept up a steady patter, “He’s no hitter; Swing! batter batter Swing! You got a strikeout Jimmy, hum it.” I swung hard at the next pitch, which hit the dirt in front of the catcher, and knocked him back. I dug in.

Pulvey was dancing around in front of our bench. Our players struggled to see past him. “Good eye, Kimball, good eye. This guy’s wild. Take your time.” I took the next pitch for a ball. Jimmy shrugged his shoulders up and down in a way that looked familiar to me. He kicked high and the next one came in fast and low. I swung, missed, heard the monk cheer, but not a word from the players perched on the St. Boniface bench. I gazed at the mound and saw a look of intensity on Jimmy’s face that was damn familiar.

Pulvey ignored me as I plopped down. He was already shouting at Bump. “Get your ass in there, Snitzer. He ain’t gonna knock you down!”

I asked this little eighth grade kid, Tony Lopello, our “manager,” to pass me the scorebook a second. I looked down their lineup. Batting fourth and pitching, Jimmy Lathrop. Jesus, the last time I saw him he was my height and sunny-faced. Sixth grade. Five years ago. “Hey Coach.” I jogged up to him.

“What?” He didn’t look at me. “Jesus Christ, Bump. Keep your eye on the g.d. ball! What do you want, Kimball?

“What are these kids in here for?” I asked.

He glanced at me quick, raising up one of his railroad track eyebrows. “Shit, I don’t know. All kinds of stuff. They mess up at school. They steal cars. They beat people up. You know. Delinquents.”

“Thanks Pulvey.” I sat down again. The Jimmy Lathrop I knew was a gentle farm kid. Apple orchards – I remembered climbing up the mountain of sweet-smelling apple crates to a tunnel that led to his hideout. We’d talk about girls and whether the Phillies would finally reach the World Series again. Baseball. He was always good at that.

We went down in our half of the first. I grabbed my glove and crossed the hard-packed infield. I passed by Lathrop. “Hey Jimmy,” I said. “Pete Kimball.” His head jerked a little, but he kept right on for their bench.

Our team made no progress against them. We misplayed grounders hopping off infield pebbles, threw to the wrong cutoff men, under threw, over threw. Once a heavy kid pounded a ball into the outfield. I was sure he was too much of a snail to get very far, so I ran it down. Snitzer had the same idea. “Outa my way you fucker!” he yelled. His blue cap flew off and his curly hair bounced around like it was trying to hold on. We nearly crashed, then watched the ball drop. We stomped around the tall grass, looking for it. The umpire was all ready to call it a ground rule double, when Snitzer (the bozo) came up with the ball and a fistful of grass. “Here it is! I found it!” The fat kid made it home, no problem.

Back at the bench again, Snitzer tapped “Take Me Out to the Ballgame” on his teeth – teeth tapping is one of his few talents. “Bump, next time you run for a ball, leave your ego at home,” said Pulvey.

Butterfield picked up his bat. “I wish he’d leave his teeth at home.”

Bump kicked at a dried out patch of grass. “Hey, this team is really gruesome. The pitcher’s psycho.”

“What you need Snitzer, is a muzzle,” said Pulvey walking away.

I faced Jimmy again in the top of the fourth inning. We hadn’t hit a lick off him, but he walked a couple of us. It was either a walk or a strikeout. “The bastard throws about ninety miles an hour,” said Pulvey. “I don’t know why the hell he isn’t on their varsity.”

I wanted to say something to Jimmy. Ask him how his sister Molly was. Ask him if his Dad still rigged up the tap so apple cider’d trickle out. Ask him if he still spent hours in his homemade darkroom. I still have the photo of me in a field holding up a gourd shaped like a girl’s breast…His first pitch slammed into my butt and I limped to first base. I watched those shoulders shrug up and down again.

When Jimmy hit the next two batters, Pulvey’s face turned red and he kept wiping his brow and mussing up his brillow-pad hair. He didn’t like his batters knocked down, but he wanted the run. Maybe the only one we’d get that day? The monk strolled out to the mound, and Jimmy stepped off the rubber, which was actually a wood plank with the paint rubbed off. The monk slung his arm around Jimmy, turned his head and spat, just like a big league manager. “Is he always like that?” I asked their third baseman. He ignored me and took a pinch of Skoal from the can in his back pocket.

I was positive the monk would trip over his robes as he jogged off the field, but he didn’t, and sure enough Jimmy settled down. Three strikeouts and he was out of the inning.

“Nice going,” I said to Jimmy as I passed him. He didn’t even look up.

The score was eight-zip by the top of the seventh inning. Jimmy’d walked a few, hit a few, struck twelve of us out. He had a no hitter going. Pulvey paced back and forth in front of us. “He’s tiring,” he said. “I can tell he’s getting tired. You gotta take advantage. Get in there, Kimball.”

My last time up probably. I stepped in again. Jimmy took his time out on the mound, inspecting his cap, the ball, hiking up his stirrups, scraping up some clay. We used to play something we called “Great Catch.” You’d throw the ball in a hard to get place, and the other guy would dive for it, leap or jump at a weird angle, then roll over, twisting and turning, at last coming up with the ball, smiling and filthy. We’d play past dusk. Did Jimmy remember? “Come on, Play Ball!” hollered the ump. Old fart probably wanted to get home.

Jimmy finally let one go and I tipped it back into the cage. “That’s the way, Kimball. Good eye. Good eye!” yelled Pulvey. Jimmy’s next pitch was so slow I missed it by a mile. I peered at him. No, he didn’t look tired. Just fidgety. He threw the next pitch as fast and wild as ever. “Ball!”

I heard the monk again. “Lay it in, Jimmy. He’s no batter!” Jimmy kicked up and threw another slow one. I’m positive I heard the monk mutter “Jesus Christ.” I hit a weak grounder that just got by the third baseman, who must have been in shock. I raced to first and beat out a single.

Pulvey clapped his hand on my back. “Way to go!” He stepped back away from the bag and their first baseman elbowed me. “Quaker prep shit,” he said. I looked over at Jimmy. He was smiling.

After I stole second base, Jimmy struck out Snitzer and our catcher. When Butterfield popped up, the game was over. Our team huddled together, fists in the center for a desultory post-game cheer. “Hurrah Res, Hurrah Res, Hurrah Hurrah E.F.S., Yay St. Boniface!” After an incomprehensible cheer from them, we stood in line to shake hands and mumble “good game” a couple dozen times. When I got to Jimmy he looked straight at me and shook my hand hard. He held on just a little longer than he had to, but when I started to speak, he moved on to the next guys. From the bus I watched him climb the hill, the last in line.